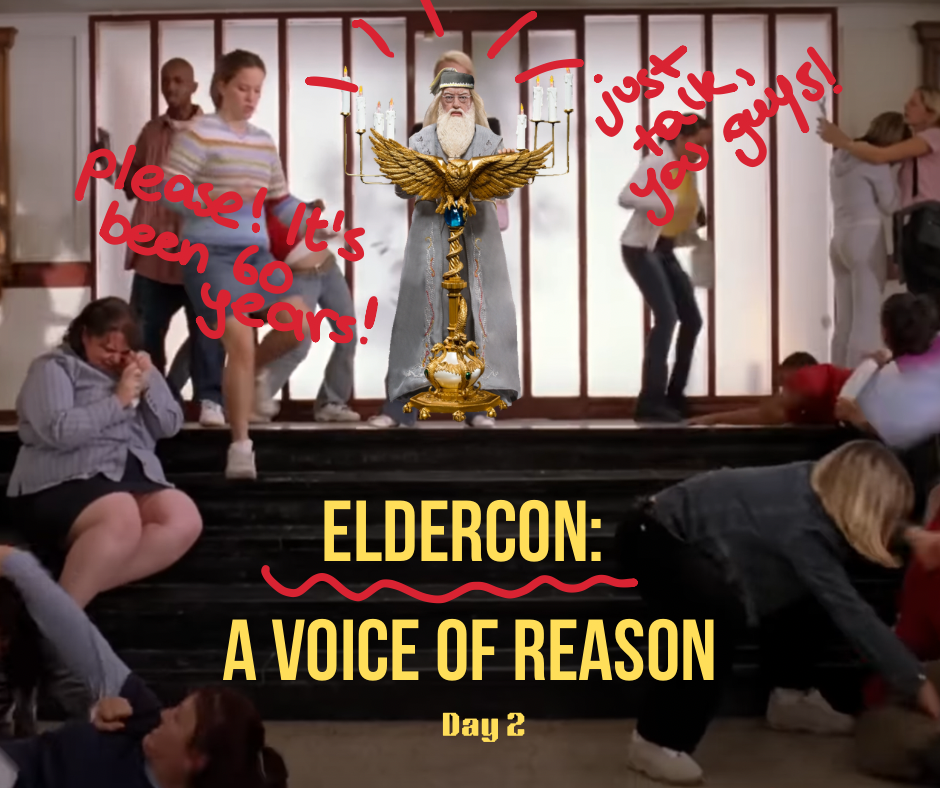

ElderCon: A Voice of Reason – Day 2

First Plenary: What’s wrong with our universities and what can we do about it?

Day 2 of the Education Conference opened on a calmer note than the day before. Maybe it was Canberra’s icy night air, helping clear heads. Maybe it was because former student and long-time activist Roderick Lyall was leading the morning plenary – commanding enough respect across factions to be heard in peace. Whatever the reason, it turned out to be the most productive plenary I’ve attended in two years.

Roderick Lyall was a student activist engaged in the NUAUS in the 1960s, serving as UWA Guild Secretary in 1963. He was also a professor at multiple universities, and was president of the Massey Branch of the New Zealand Association of University Teachers.

Money. Must Be Funny.

Lyall began with a powerful reflection on the surreal experience of still fighting the same battles sixty years on. “It seems very strange to be talking about this today,” he said, “when the world is closer to a nuclear war than ever before.”

He spoke of his concern – shared by many – over the current direction of tertiary education. He outlined how universities have shifted away from their original missions of fostering knowledge and are now profit-driven institutions, with responsibilities divided between academic and financial aims. This shift, Lyall argues, has led to targeted attacks on arts and humanities departments, as funding is funnelled instead into research that aligns with corporate or government interests. Increasingly, academics are pressured to secure research funding rather than focus on teaching.

“Why do they find them [arts and humanities] so dangerous? Because we teach people to think.”

“Why is Trump going after universities? Because we teach people to think.”

He also criticised the growing obsession among vice chancellors with university rankings, questioning why some of Australia’s most prominent institutions are sliding in these tables year after year.

On a separate note, Lyall recalled the original purpose of academic tenure: to compensate for the lack of job opportunities with long-term security outside of the sector. In stark contrast, around 40% of academic staff in 2024 are on short-term contracts. This, he argued, affects not just the working conditions of staff but the quality and continuity of students’ education – and even whether certain courses can continue to exist at all.

“This trifecta of discontent which has effectively destroyed much of the academic profession,” he said, noting the ongoing deterioration of staff-to-student ratios.

Studying! What’s the point?

Lyall then asked everyone working a job while studying full-time to raise their hand. Nearly everyone did. In the 1960s, he noted, this would have been unheard of. “It was very rare for a full-time student to have a job outside education,” he said. Now, thanks to the cost-of-living crisis, the completion rate, engagement, and value of the university experience are all under threat.

“Then they have the nerve to talk about job-ready graduates.”

What Now?

Lyall offered two central solutions: 1) strengthening democracy, and 2) building a sustainable future. He urged the National Union of Students (NUS) to forge deeper alliances with student cohorts and campaign alongside the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU), emphasising the shared stakes.

“You and the academic staff have a huge common interest … everyone gains from a better government investment to the tertiary education.”

Discussion

When discussion opened, a Unity speaker asked whether engaging university management should be the first step before resorting to conflict. “Absolutely,” Lyall replied. “That’s where it has to start. If that doesn’t work then think of alternatives.” He encouraged the NUS to develop practical guidance sheets to assist campus unions during negotiations with vice chancellors and senior management.

Responding to a vague reiteration of his points by a SAlt speaker, Lyall doubled down: the NUS should demand more from the Labour government – “Why not push for more?” – and communicate far more effectively with its student base. He also stressed the importance of separating one’s political affiliations from their responsibility within the NUS, clearly alluding to factionalism in the room.

Another student raised the issue of declining student engagement. “How do we convince them to want academia back?” they asked.

“Constant propaganda is probably the answer,” Lyall said, half-jokingly, before referencing the importance of student media.

“Most students just want to get on with their lives … it’s about doing stuff that touches them.”

He closed with a simple final message:

“No other advice than to just keep talking.”