Short Film Triple Feature Review - Film Review Friday

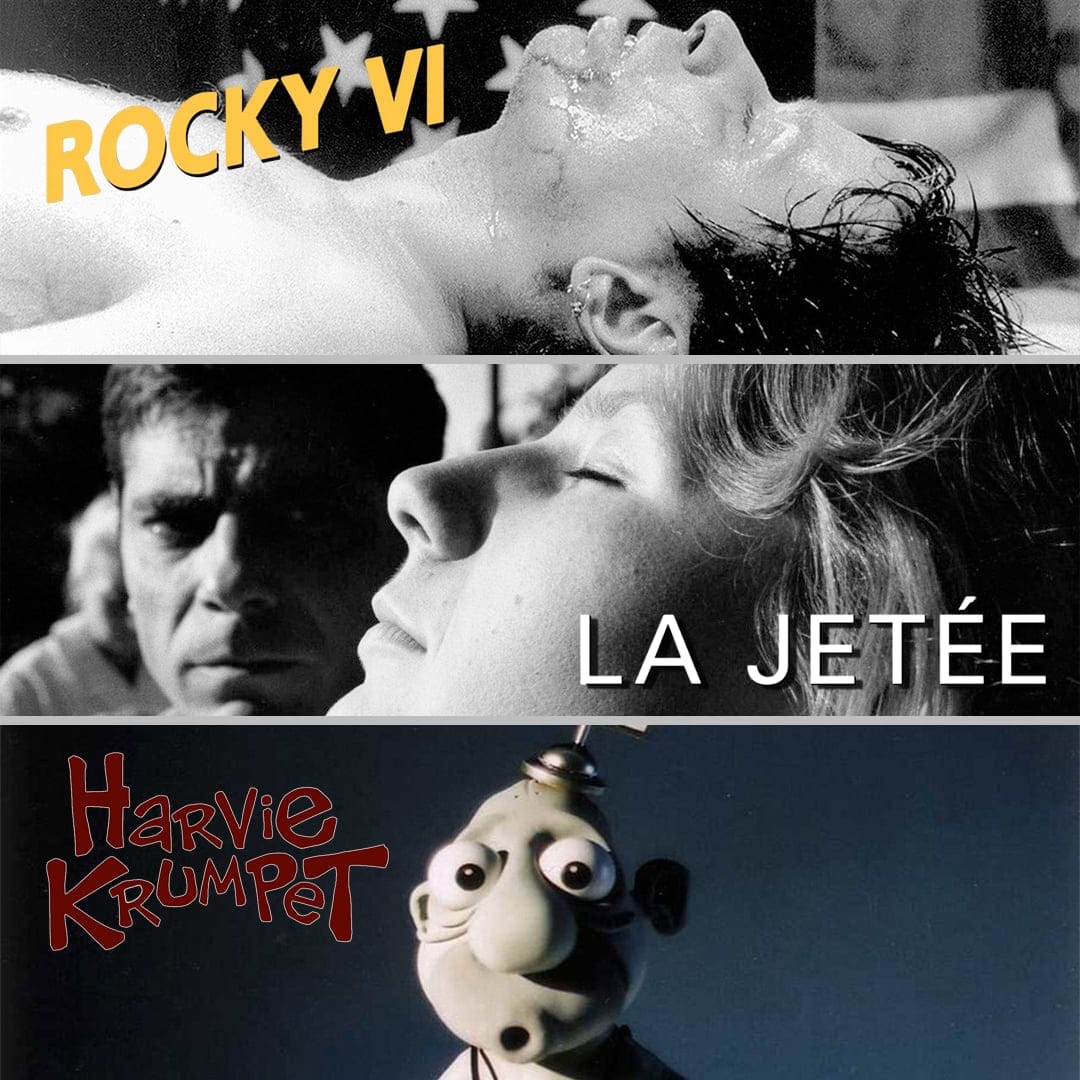

'Rocky VI' dir. Aki Kaurismaki (1986) - Reviewed by Mason Horsley

The 1980s were an amazing decade for cinema. Within those 10 years, filmmakers gave us some of the most defining pieces of the art form. ‘The Shining’, ‘Blade Runner’, ‘Back To The Future’, ‘Akira’, even one of the best love letters to film, ‘Cinema Paradiso’! Along with these masterpieces, however, came movies dedicated to American patriotism, determined to portray the United States as the greatest country in the world, sometimes to unrealistic standards. That’s where ‘Rocky VI’ comes in.

Aki Kaurismaki sought to tear that all down with one short film, to satirise the formulaic approach of American films, particularly Sylvester Stallone’s ‘Rocky IV’. Of course, this approach was used to champion the American Way as the Cold War raged on; Americans refused to bow down to the Soviet Union’s threats and used cinema to show their patriotism. However, the argument Kaurismaki tries to make is that ‘Rocky IV’ pushes that liberty beyond the limit, that there is no way Rocky Balboa would ever defeat a colossal steroid-pumped Russian in the ring. Just as Karausmaki inverts the title, he also inverts the story, even going so far as to name his villain (or hero?) the reverse pronunciation of the title character.

‘Rocky VI’ follows the fighters Rocky and Igor as they both make their separate trips to Helsinki for the next cinematic bout. The film is shot in black-and-white and features a song simply called ‘Rock’y VI’ by the Sleepy Sleepers which is played in the same pop-rock style as Survivor, but with a bit of James Brown orchestra backing up. The second half presents the fight, with bulging behemoth Igor in one corner and a skinny and short Rocky in the other. Igor effortlessly kills Rocky in the ring and is driven back home as he strums a ukulele with boxing gloves.

I really enjoy the camerawork and visuals; the black-and-white look really pushes the idea (intentional or not) that this could be a Russian-made bootleg to raise their own country’s morale against the endless pro-American film movement. The titles also help, doing away with flashy, international-conflict-focused openings and instead sticking with clear simple text on a black screen.

Sakari Kuosmanen plays Igor, with big fuzzy brows stuck on, and does a great job parodying original Rocky villain, Ivan Drago. Some shots in ‘Rocky IV’ seemed to suggest that Drago wasn’t all there mentally and that his wife was the big thinker. Kuosmanen takes that image and wonderfully amplifies it, portraying Igor as a moronic drunkard who does what other people tell him to. It’s a small performance, but he does the job extremely well.

Antti Juhani Seppala of the Leningrad Cowboys (a Finnish band Karausmaki directed music videos for) plays Rocky and while he doesn’t successfully parody Stallone, he does an amazing job portraying the American everyman. With Stallone’s films, the narrative was pushed that both he and Rocky were less-than-average Americans, and while that was true for the first 2 or 3 films, by the 4th, it was clear that both the actor and character were in upper-class positions. Both now had the money to hire personal trainers, purchase quality exercise machines; like Apollo Creed said in ‘Rocky III’, “You had that eye of the tiger, man… now you gotta get it back, and the way to get it back is to go back to the beginning.” Since Stallone practically forgot that lesson for the 4th film, it seems that Kaurismaki took it back to the beginning himself.

The soundtrack comprises of a single song, beginning with melancholy strings before pumping into the rock-pop melody and finally finishing with the same strings from the beginning. Throughout the song, quotes from both the Rocky films and American history are sung. For example, the quote that triggers the central melody is “I have a dream…free world!”. Other quotes might be from the perspective of characters from the original film, like “Don’t kill me!” and “I will break you!”. It’s a fascinating blend of themes and perspectives, especially when it turns into a stereotypical American anthem, “You want money, you want sex, you want violence, what do you want next? Hahahahaha, free world!”

The film is on YouTube right now and I highly recommend it. It’s an easy quick watch and it’s quite a relic.

Mason’s Top 3 Reasons to Watch ‘Rocky VI’

- It’s only 9 minutes, a quick log for your Letterboxd!

- An incredibly interesting critique on Cold-War-era cinema and to an extent, Stallone’s own filmography, including ‘Rambo’ and ‘The Expendables’

- A curious introduction into Finnish music with the soundtrack.

'La Jetée' dir. Chris Marker (1962) - Reviewed by Daniel Fagan

“Nothing sorts out memories from ordinary moments. Later on do they claim remembrance when they show their scars.”

The short film may be the shorter of the form, but it can condense the whole world and our all too brief human experience into a breathtaking pearl. No short in the history of cinema takes this idea and far exceeds it in ways never before imagined and never since repeated quite like Chris Marker’s 1962 experimental masterpiece, La Jetée. The 422 still photographs comprising La Jetée weave hypnotically with score, sound design, and narration to form a tapestry of human emotion. This masterful tale of time travel in the post-apocalypse is cinema’s most intimate portrayal of existence, despair, and memory in a mesmerising testament to the enduring power of love and human connection.

La Jetée follows a man scarred by memory. In the tunnels under a Paris shattered by an atomic WWIII, there is little else for the survivors. These survivors are prisoners to ever-fading, fragmentary thoughts of a world long gone, to the radiation of the one that has replaced it, and to the mysterious scientists who wish to experiment on those with the strongest memory of the past and send them through time. Time is, of course, the one unstoppable true enemy of all things, and even if we can manipulate it for a moment, and escape the time we’ve been assigned, we cannot hide from the silent merciless murderer.

As a child, on the jetty at Orly Airport, The Man witnesses a murder. The image is too grisly to recall and in its stead he focusses on fragments of beauty surrounding the horror. The setting sun, forever frozen at the end of the jetty, and a woman’s face with a mysterious Mona Lisa smile. It is the woman’s face, with its indecipherable emotion, which comes to scar The Man – her face is his only memory of peace. As time pushes on in the squalor of the survivor’s world, he questions whether it truly is a memory or simply an imagined moment of tenderness in a world spiralling to madness.

The scientists below Paris intend to send people through time with the hope that the key to humanity’s survival can be found in the past or future. They select The Man as their next guinea pig, place a mask over his eyes as though he were asleep, and send him into the past through his strongest memories to prepare his mind for the shock of entering the future. Memories of the past ooze through The Man, and after over two weeks of torment he arrives at the Orly jetty, silent and empty, but for the woman he seeks who smiles at him from the static museum of his memory.

The Man tracks the mysterious woman through his memory, and when they meet, it is as though they are the only people in existence, as though time were creating itself from their connection and radiating into eternity. They stroll through gardens, count the rings on giant felled trees, and fall asleep smiling mysteriously in the sunlight. The Man is pulled back to the dingy tunnels of the present, then sent to a different moment, but again the woman is there. They spend aeons timelessly, statically, wandering the streets of Paris, and they fall into a beautiful silent romance.

At the height of this romance the film elevates itself to an unbelievable, painfully human, artwork. In this moment all seemingly disparate elements and philosophies fade together and in one motion take the audience’s breath away. This moment is accompanied by the twitter of unseen birds. In a sonic world of narration, heartbeats, and half-caught sporadic whispers of a foreign language, the sound of birdsong is alien. It forces the audience to concentrate and draws their eyes in total focus to the screen for those few glorious seconds wholly encapsulating the human experience - our memories, our fears, our hopes, our need for connection, for each other, and for love.

La Jetée is as close to poetry as film has ever reached. It is a miracle.

'Harvie Krumpet' dir. Adam Elliot (2003) - Reviewed by Emma Cranby

I recently made the decision to start watching more Australian film and television. As good as overseas media can be, I always find there’s just something about the Australian stuff that can’t be replicated anywhere else. So of course, I couldn’t have been more pleased when short films were proposed as the subject of our triple feature this week. What a great way to watch more Australian films, I thought – and it didn’t even demand too much time or effort! Unfortunately, my knowledge of short films is hideously limited, and when I tried I couldn’t think of a single Australian short film.

My own knowledge having failed me, I turned to that great repository of knowledge, the one and only Google – and it was this that led me to the film I’m reviewing this week: Harvie Krumpet. It’s produced, written, directed, narrated, and animated by Australians – and it’s remarkable. The short film follows Polish-Australian Harvie Krumpet throughout his life, from his difficult childhood in Poland to his migration to Australia and efforts to make a life for himself there, despite the significant struggles he continues to face. Although Harvey lives with Tourette syndrome and asthma, even facing cancer at one point that results in his losing a testicle, he is able to build a family, marrying nurse Val and adopting a daughter, Ruby. Even when Val dies and Harvie is admitted to a retirement home, he is able to find solace in friends, and although the film doesn’t shy away from acknowledging the hardships life often faces people with, it is ultimately a poignant take on redemption and meaning. It is profound without ever being unnecessarily sentimental, confronting concepts like love, death and family head-on.

Managing to do this – and do it so effectively – in only 20 minutes is a remarkable feat, and no less so for the fact that the film is made entirely with plasticine models. At least in part because of this, the film is visually highly distinctive, with expressive, exaggerated characters and peculiar scenery that nonetheless stops just short of being grotesque. This uneven style is a characteristic of director Adam Eliot’s filmography, with the large eyes and features of the models that give them such a memorable and almost eerie quality being necessary to allow him to manipulate the material properly.

Beyond its remarkable visual aspect, Harvie Krumpet is also worth noting for its audio. The narration is provided by Australian actor Geoffrey Rush, known for features like Shine and the Pirates of the Caribbean series, and his evocative, mellow tone fits the film perfectly. Although there is little dialogue, what does appear is authentic, and lends the film a definite realism, even despite its animated nature, that allows it to be all the more impactful.

Given the excellence of its individual components, then, it’s perhaps not so unexpected – though it’s certainly no less impressive – that the film in fact won an Academy Award, receiving the Oscar for Best Animated Short Film in 2004. Although this is only the second or possibly third short film I can recall ever watching, it’s an undeniably great piece of media, and if it’s Australian short films you’re after – or any short film at all – I’m certain you won’t go wrong with a viewing of Harvie Krumpet.